The Campidoglio Engraved

Approaching the Campidoglio

The Capitoline hill was one of the famed seven hills of Rome, and gives us the word "Capitol" for the seat of the US government in Washington, D.C. In the Renaissance (as today), it was known in Italian as the Campidoglio.

This lovely etched view by Willem van Nieuwlandt, who published a series of prints of Roman scenes in Antwerp, shows how one might approach the Capitoline hill from the Roman Forum, via the slightly winding path leading up the incline on the left. To the right is the arch of Septimius Severus.

Van Nieuwlandt, a Dutch artist (1584-ca. 1635) was one of many northern artists who traveled to Rome and made sketches of the sights there.

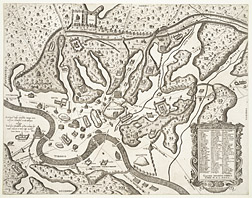

A Renaissance view of the ancient city

This Renaissance map presents a conjectural view of ancient Rome stressing topographic relief―in other words, the seven hills. It shows a rather bare area labeled "Capitolium" that includes the Temple of Jupiter and little else―reflecting Renaissance uncertainty about exactly what buildings would have been situated where in ancient times.

Renaissance antiquarians considered the Capitoline Hill to be the most prominent, and first settled, of the ancient city. This is reflected in Renaissance visions of the earliest history of the city, depicting a square layout in which only the Capitoline and Palatine Hills are enclosed within the city walls.

This map is a copy, engraved by Ambrogio Brambilla and published by Claudio Duchetti, of an earlier map engraved by Etienne Dupérac and published by Antonio Lafreri. Lafreri was Duchetti's uncle and the publisher of the Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae prints. He also published numerous maps, many of which were often bound together in similar collections known as the Geographia.

For an entirely different view of the ancient Capitol, see the next image.

The ancient Capitol in action

This is a very large engraving, made up of three folio-sized sheets joined together. It represents a rather fantastical Renaissance view of the ancient Roman Capitol: it looks more like a stage set with actors (including gods such as Mercury and Cupid) than a scholarly, classical view of the ancient city. It also recalls other prints that depict scenes of everyday life in the early Renaissance. The theatricality of this image carries over into others that use the backdrop of Rome to stage dramas of various kinds [see exhibition case 24].

We do not know what artist designed or engraved this beguiling image. Impressions (copies) of it often appear in Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae collections; it was published by Antonio Salamanca, the print publisher, originally from Spain, who was Antonio Lafreri's sometime rival and later business partner.

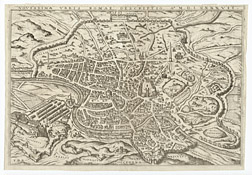

A map of Renaissance Rome

This map provides a panoramic view of the city in the late sixteenth century. A legend at the bottom of the map indicates the main features by category―temples, streets, etc. On the Campidoglio, a label indicates the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius that was (and still is) the centerpiece of the piazza: "Statua Marci Aurelii." For more on this statue, see the next two images.

Note that a later viewer has added annotations to the map and colored the Tiber blue. Several of the prints in the Speculum collection at Columbia University's Avery Library also have water that has been colored blue. Both collections were sold by the same book dealer in Berlin (S. Calvary & Co.), in the late nineteenth century; this might suggest that all the Chicago and Columbia prints were once part of a single gigantic collection, or that the blue-colored prints in particular belonged to one person and were acquired by Calvary and then split between two different lots.

The statue of Marcus Aurelius

The equestrian statue of the philosopher-emperor, Marcus Aurelius, is the centerpiece of the Piazza del Campidoglio. During the Middle Ages, it was thought to be a statue of Constantine, the first Christian emperor of Rome. This probably accounts for the survival of the statue during a period in which other bronze statues, viewed as pagan idols, were melted down and reused as raw material.

In the Renaissance it was a new arrival to the site. The statue was moved to the Campidoglio from the piazza in front of the church of San Giovanni in Laterano in 1538 by Pope Paul III, as part of plans for a new design for the area. Michelangelo produced the overall design, but was not thrilled at having to incorporate the statue. Nonetheless, he provided the statue's pedestal as part of his new design.

Traditionally the design is understood to have been commissioned by Paul III in preparation for his meeting with the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V in 1536 (a reconciliation between the empire and the papacy after the 1527 Sack of Rome). But evidence suggests that the Roman civic government also played a major role; the area was, in fact, devoted to civic and not papal concerns.

It took many years and the contribution of many builders for the square to acquire any semblance of Michelangelo's plans for it.

Today the original statue is housed in the Capitoline museum, and a copy stands in its place.

Another view of the statue of Marcus Aurelius

The previous image displayed the side of Michelangelo's pedestal that identified the statue as that of Marcus Aurelius. In this one, we see the inscription that appears on the opposite side of the pedestal from the preceding image. What is strange is that the statue retains the same orientation, with the horse and rider facing to the left. If it is the opposite side of the statue, we should see the horse and rider facing the other way.

This may be the result of the artist's drawing being reversed when turned into a print, since printing plates were oriented in reverse vis-a-vis the printed images they produced. The text on the pedestal, however, has been carefully (if not too adeptly) copied so as to appear correctly oriented in the resulting engraving. This image, part of a large set of engravings of statues that are organized by their location at the time the set was produced, appears in a sub-grouping of statues located at the Campidoglio, in the open air or in the Palazzo dei Conservatori (the seat of Rome's municipal government).

The inscription cites two popes, Paul III, who had the statue moved to the Campidoglio, and Sixtus IV, who had had the statue reinstalled at the Lateran in the late fifteenth century.

Map of Rome

This map was published around 1597 but was likely copied from an earlier map, so it is not up to date. It shows schematically the beginnings of the implementation of the Renaissance plan for the site: the statue of Marcus Aurelius stands within the oval area that Michelangelo designed for the piazza. With some inaccuracies (partly due to the small scale), it corresponds approximately to the view in the next image, which was made around 1560.

The Campidoglio around 1560

This engraving has been attributed to Nicolas Beatrizet, a printmaker from Lorraine who worked in Rome and frequently produced prints published by Antonio Lafreri. It shows the Campidoglio around 1560. The Palazzo Senatorio, to the rear, has a new staircase designed by Michelangelo, with a reclining river statue on either side, but no other updates.

The Palazzo dei Conservatori, to the right, also retains its earlier facade (in fact, the image presents it with a simplified version; it had twelve archways, not six).

The colossal head of Constantine, fragment of a gigantic ancient sculpture, peeks out of the portico of the Palazzo dei Conservatori, on the right and to the rear.

Note the changes that take place in the rear and right palaces between this image and the next.

"As it is now"

Nicolaus van Aelst was a Flemish engraver who published copies of Speculum prints, and also his own depicting Roman obelisks, churches, and other sites, in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. This one is dated 1600. The print is labeled "Capitolii Romani vera imago ut nunc est," meaning "True image of the Roman Capitol as it is now." This title suggests an acute awareness of the changing face of Rome's urban landscape at the end of the sixteenth century, and the demand by visitors and collectors for accurate representations of the scene that they themselves saw on the spot.

To the rear, the Palazzo Senatorio (the Senate palace), and to the right, the Palazzo dei Conservatori (the seat of Roman civic government), were built in the later sixteenth century. To the left, the statue called "Marforio" [A113 link?] appears, restored and installed as a fountain; it was placed there in 1594, by the architect Giacomo della Porta, with the patronage of Pope Clement VIII. The fountain sits at the future site of the Palazzo Nuovo, which appears completed in the next image in the itinerary; the Marforio fountain was removed in the mid-seventeenth century, and eventually placed inside the palazzo.

The mid-seventeenth century and the de' Rossi

In this updated version of the previous engraving, the piazza appears in the form in which it would remain for approximately three hundred years. The three palazzi have been completed and the oval at the center of the piazza has been paved with a radiating pattern.

This print was published by Giovanni Giacomo de' Rossi, member of the family that dominated print publishing in Rome in the seventeenth century. De' Rossi apparently acquired Nicolaus van Aelst's copper plate (see A77) and had portions of it re-engraved to update the scene―in particular, adding the Palazzo Nuovo to the left and the paved pattern on the ground. This was one among many plates that he acquired and republished under his name.

Michelangelo's paving stone design had actually been much more complex, an elaborate design of intersecting arcs that was never carried out under the popes, perhaps because it was perceived to have questionable symbolism. Only under Mussolini, in 1940, was the design implemented, as part of the Fascist reinvention of Roman classicism. ( Click here for a modern view. )

The Tiber

This print depicts the statue of a personification of the Tiber river installed under the staircase of the Palazzo Senatorio, visible in several of the views in this itinerary. As the inscription notes, it was originally a representation of the Tigris in Mesopotamia, but was changed into a representation of the Tiber with the addition of a wolf nursing the young Romulus and Remus, founders of Rome. For an image of the famous statue of the wolf, which also stands in the Campidoglio, see the next image.

Giovanni Battista Cavalieri published engravings of many of the most famous statues of Roman antiquity. His collection was later expanded and republished by several other publishers. They are organized by the collection in which the statues are found, so the statues at the Campidoglio are grouped together (Chicago Speculum C804, C805, C806, C807, C826, C827, C828, C829, C830, C831, C832, C833, C834, C835)

The Capitoline Wolf

This print depicts one of the most famous statues on the Campidoglio. The bronze statue represents a female wolf nursing the founders of Rome, Romulus and Remus. The two infants were added to this ancient Etruscan statue in the fifteenth century, probably in order to reinforce its association with the city's origin myth and its power as a symbol of Rome.

Other sculptures associated with the Campidoglio include the "Spinario" (A114); the Trophies of Marius ( A123, A124, B351, B352); Roma Victrix ( A90); the Triumph of Marcus Aurelius ( A116); the Battle of Amazons ( A100 - A101) and a frieze of sacrificial instruments ( A128).

Bibliography:

Philipp Fehl, "The Placement of the Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius in the Middle Ages," in Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 37, 1974 (1974), pp. 362-367

Charles Burroughs, "Michelangelo at the Campidoglio: Artistic Identity, Patronage, and Manufacture," in Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 14, No. 28. (1993), pp. 85-111.